Zody Burke is an American multimedia artist living and working in Tallinn. Read her interview with us and see her work at Estonian Academy of Arts exhibition TASE`24 graduation show in Tallinn Art Hall derelict basement open ’til the 14th of June.

I know it’s tough, but could you find a way to summarise what's your exhibition “The Under-Earths Spin'' about?

I’m not sure how to answer in a way that makes sense, because it’s about so many different things! It’s about a Soviet Estonian mural and the artist who painted it, it’s about the feeling of being adrift between two strange countries, it’s about folklore, mining, railroads, and rollercoasters. One way to explain it better might be to talk about my research method. Recently, I’ve been playing around with this idea I’m calling ‘psychocartography’. It’s a bit like psychogeography, the Situationist practice that explores our relationships to urban environments, and architecture’s effects on behavior and emotions. Psychocartography – cartography being the practice of map-making – is something I see moving psychogeography a step further into a more global context. I want to consider the material history of the literal stone, steel, and oil that builds cities, where they came from, who dug them up, and how they got here. I want to think about the pipes underground and fiber optic cables under the sea that bridge infrastructure, cultures, and landmasses together. I also want to think about what the presence of something like a retail store or fast food chain implies, about a huge expanse of connections branching across the world, materially, economically, and relating to labor. This is a concept that I made up, so basically anyone’s definition of it would be just as good as mine.

To put it simply, I’m interested in teasing out hidden connections from things that might not have a totally tangible, visible relationship. Kind of like connecting points on a map. So, the exhibition was about this, more or less. I had a set of interesting things that inspired me, which I could sense were connected in some way, and I tried to connect them.

In your thesis, you talk about interesting relations between trainhopping and amusement parks.

Could you tell us briefly how the history of railroads ended up being capitalized by the society in the form of a roller coaster?

A big part of the research that went into the written thesis was about finding the link between the railroad and the rollercoaster, which are related when you think about it. The history is, that there was a coal mining railroad built in the mountains of Pennsylvania in the 1850s, which the miners started riding for fun after hours. After the invention of the locomotive made this particular rail line obsolete, it was turned into a theme park of sorts, and this coal mining line became the world’s first rollercoaster. The fancy new commuter railroad lines connecting New York and Pennsylvania shipped in tourists to ride the obsolete railroad-turned-rollercoaster for fun. The relationship between industry and leisure culture can be mapped in this way. You know, there are a practically uncountable number of cities, towns, etcetera in the USA that owe their entire existence to the railroad. It’s a really potent metaphor for me in the way that it visually, literally, culturally, and economically connects points on a map. Something I’m interested in is moments in history where industrial society “progresses” past a certain point and you start to notice these mirrorings in leisure culture. It feels very hedonistic, these sorts of celebrations of mankind’s plundering of the earth’s resources and victory over the laws of nature, making new types of pleasure activities possible. I referred to the rollercoaster as the doppelganger of the railroad, as a kind of hedonistic twin that can’t exist without the other. But I love the metaphor of the rollercoaster as a closed loop, a railroad that goes nowhere.

Seeking thrill in amusement parks seems more "safe" than train hopping. Do you think that the second option is raising the stakes when a simple joy ride is not doing it anymore?

Could you tell us more about your experience in train hopping?

When you’re in a theme park, you’re expected to behave in a very sort of controlled way, it’s almost like a microcosm of late capitalist consumer society, there are particular routes and paths you are expected to take, lines to wait in, and many off-limits areas. No outside food or drinks. In any given American theme park there is no shortage of surveillance as well, you know, security cameras and guards making sure the rules are followed in this encapsulated ecosystem of absolute decadence. It’s a philosophy of consumption along precise trajectories.

Around the time when theme parks started popping up in the early 1900s, as kind of an antecedent to the Industrial Revolution, the people who attended them were working-class folks, people with dangerous jobs in factories. This was before workplace safety was standardized. This interesting thing started happening when these factory workers would pay for what was called “ersatz risk” - the thrill of danger without actual physical consequences - they loved rollercoasters because they mirrored what must have been persistent anxiety about the dangers of industrial accidents in their day to day lives. We enjoy rollercoasters because what feels physically like a near-brush with death is chemically transfigured into pleasure, if we trust that we are safe, in other words, if we put our bodily integrity in the hands of others.

I think part of the appeal of hopping freight trains is rooted in a rejection of this ethos of consumption along precise trajectories, the omnipresent structuring force pervading nearly every aspect of American public life. Taking your life out of the hands of your handlers makes it so there’s no one left to sue but yourself if you get hurt. It’s scary and it’s radical to put yourself in a position where you are fully responsible for your safety, which of course we all are at all times, but the common narrative would have us believe otherwise. And of course, the safety net of society’s regulations is always an illusion, for everyone, but for some more than others. I think it’s good to remember that.

The thrill of danger without actual physical consequences - they loved rollercoasters because they mirrored what must have been persistent anxiety about the dangers of industrial accidents in their day to day lives.

In your work you find many relations between the East and the West (Estonia and the USA), was this something that you had intended before coming to Estonia or it happened when you got here? Could you bring some examples?

I’ve never felt as American as I do after moving to Estonia. I guess it’s predictable that getting some distance has allowed me to more critically examine the place I’m from, for better or worse. Also probably predictable is the fact that I knew next to nothing about Estonia for most of my life, the American public education system is not world-renowned for a reason. Most Americans can’t distinguish between the Balkans and the Baltics. When I got here, of course, there were differences, but one thing that surprised me was how similar things were. These similarities become extra visible when you move away from the city; suburbs have similar characteristics everywhere I guess.

I’m interested in landscapes of suburban sprawl that don’t have an inherent sense of cultural identity – highways, gas stations, cul-de-sacs. It creates a sort of eerie feeling of displacement, like you could be anywhere. I like to play with this feeling in my work. Maybe I enjoy this sort of romanticism because I’m from one of the most densely populated cities in the world, but I feel like there is so much strange energy in the suburbs, whether in Estonia the USA, or elsewhere.

I keep thinking about one of the first scenes in Blue Velvet, where the camera pans down from an otherwise unremarkable scene in Anywhere, USA, and goes under the ground, where you can see the grotesque and visceral starkness of the dirt and the worms. Lynch has talked about the presence of this other more naked and brutal world – here, I’ll find the quote. “I learned that just beneath the surface there’s another world, and still different worlds as you dig deeper. I knew it as a kid, but I couldn’t find the proof.It was just a kind of feeling. There is goodness in blue skies and flowers, but another force–a wild pain and decay—also accompanies everything.”

There’s sort of a pervasive, absurd, banal brutality that lurks just under the surface of ‘sanitized’ civil life – I don’t know if I’m necessarily successful in embodying that feeling in my work, but I think about it a lot.

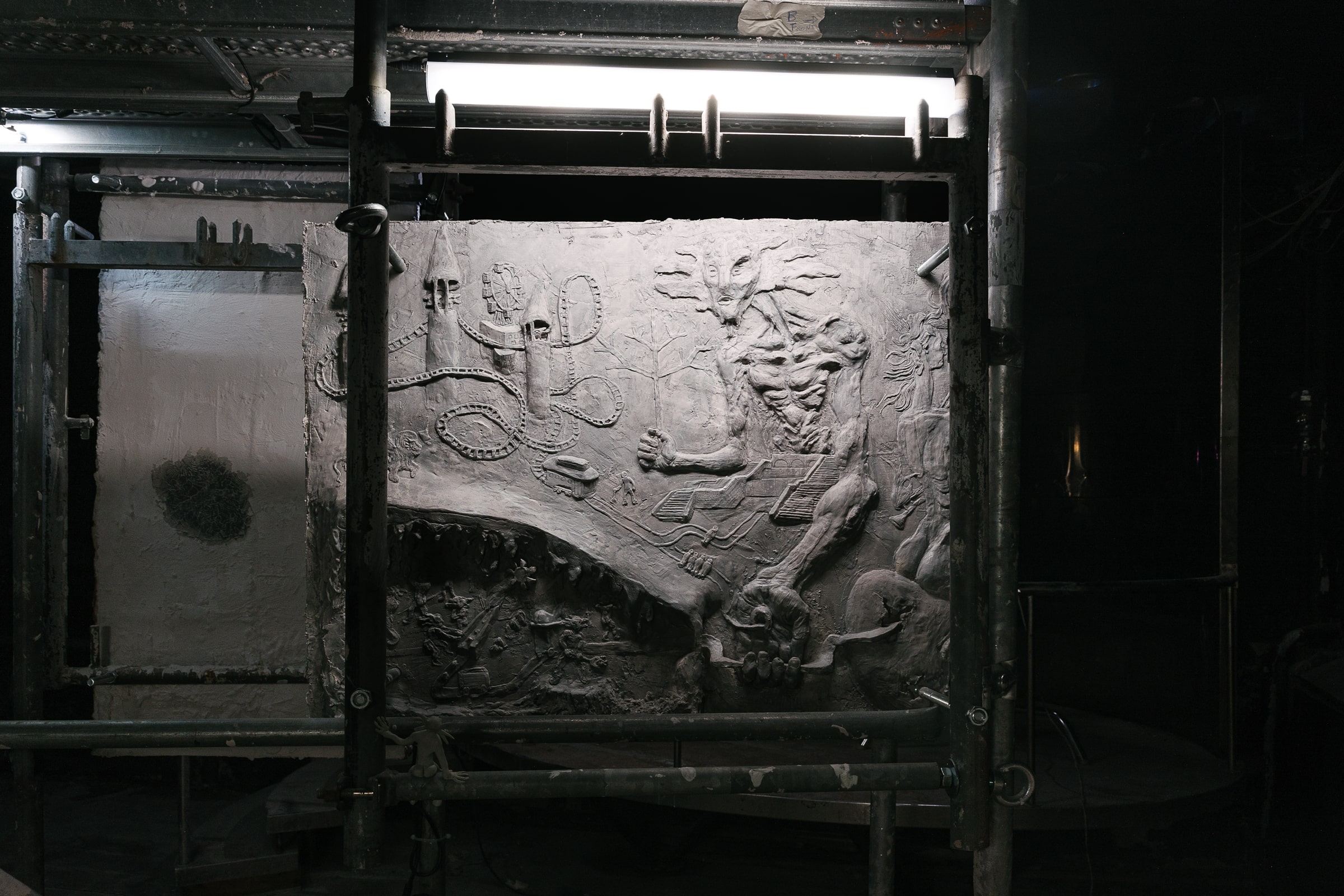

When looking at your (sculptural) murals they seem to be telling some sort of a story or a narrative. Could you tell us about them?

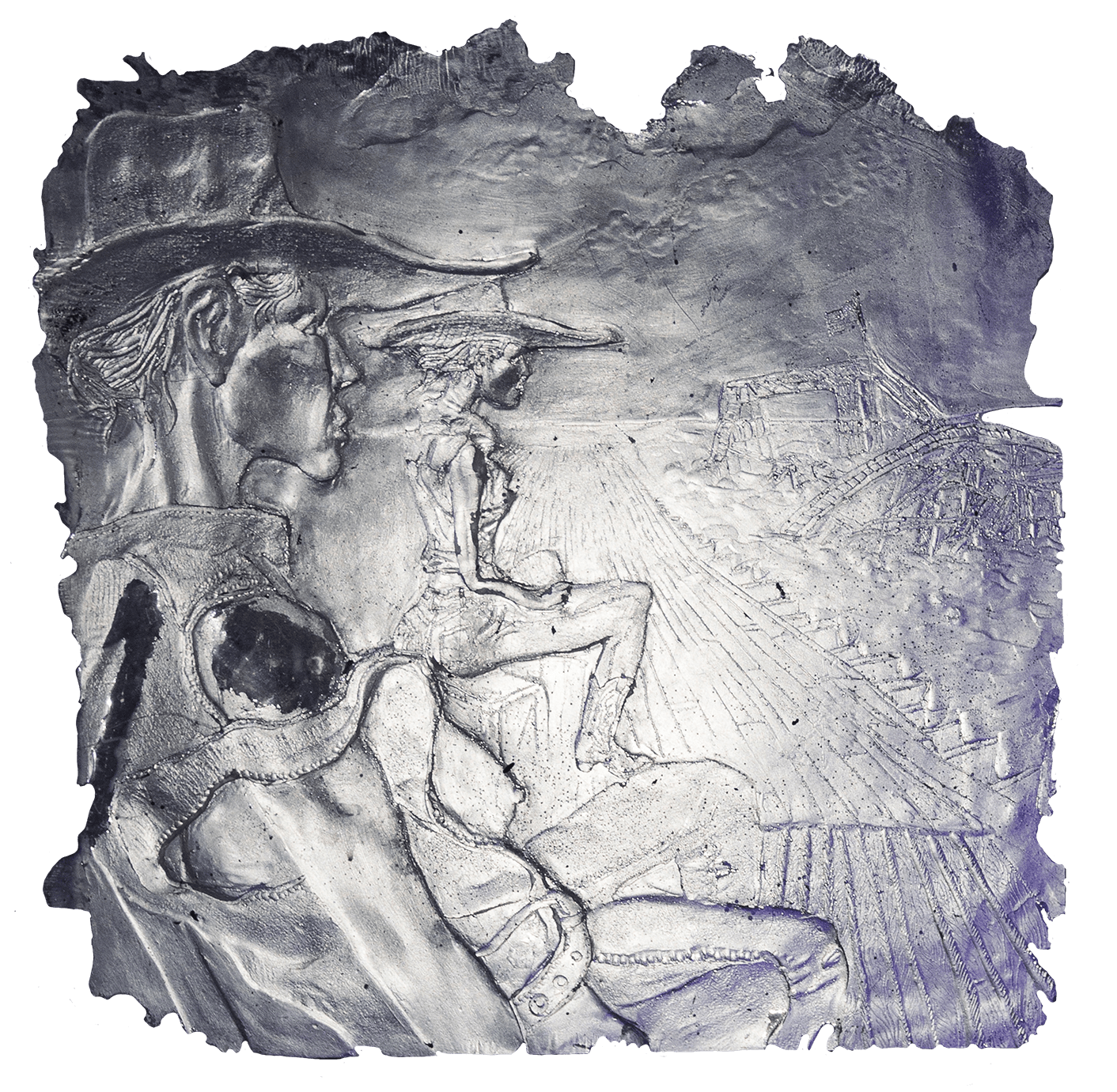

I started making art as an illustrator, and I made comics for several years. Because of this, I feel like storytelling or narratives are just a reflexive behavior in my practice, that I couldn’t avoid if I tried. There’s always something happening that starts somewhere and ends somewhere. The two sculptural murals, or high reliefs, in The Under-earths Spin … I see them as sort of spatial vignettes, there’s the very clearly Estonian one, and the other one is a little more dubious. I started it as a sort of American scene, with elements inspired by my interest in suburbia as I just mentioned. The two figures in the relief, the hunter and deer woman, are taken from this fascination I had with hetero-cringe couples’ Halloween costumes. There’s a trope in the States I guess where the boyfriend dresses up as a hunter, and the girlfriend as the deer, and I’ve found photos of different couples posing in this way where the woman-deer is playing dead after the hunter has killed her. It’s fascinatingly grotesque.

The Estonian scene is my interpretation of Kreutzwald’s Maa-alused story, in which an ordinary guy named Hans is taken into a mountain by a benevolent spirit creature named the Pine Man who shows him how wealth is created. The maa-alused are elven creatures who work in the Pine Man’s mines, and the fruits of their labor are hoarded in secret caverns by the Pine Man. When Hans asks why the Pine Man doesn’t share his wealth, he replies that if he did, “the world would surely perish in laziness, for man is created to work and struggle.” The maa-alused, as non-human workers, escape our empathy in this story, making it clear how easily we can overlook exploited labor when the workers’ humanity or agency is obscured.

In this high-relief sculpture, the Pine man is depicted with the features of a Jüri Arrak figure, as are the Maa-alused miners in the bottom corner. I wanted to give them a very clear semiotic relationship with Estonian folklore imagery. The character Hans is depicted as the operator of the trolley problem, a meme that symbolizes a choice that “average” people are presented with… to mobilize their small amount of agency in the service of the oppressed or give it away to the ruling class, while acknowledging that all choices have consequences. On the right is a figure from a Concordia Klar print who I’ve depicted as half-avian and brooding over an egg. In this context she might symbolize a passive, motherly earthly deity, looking away from a scene she has no influence over. The egg is a recurring motif in surrealist art which symbolizes the enduring mysteries of life. I guess you could say that symbolism is pretty important to me.

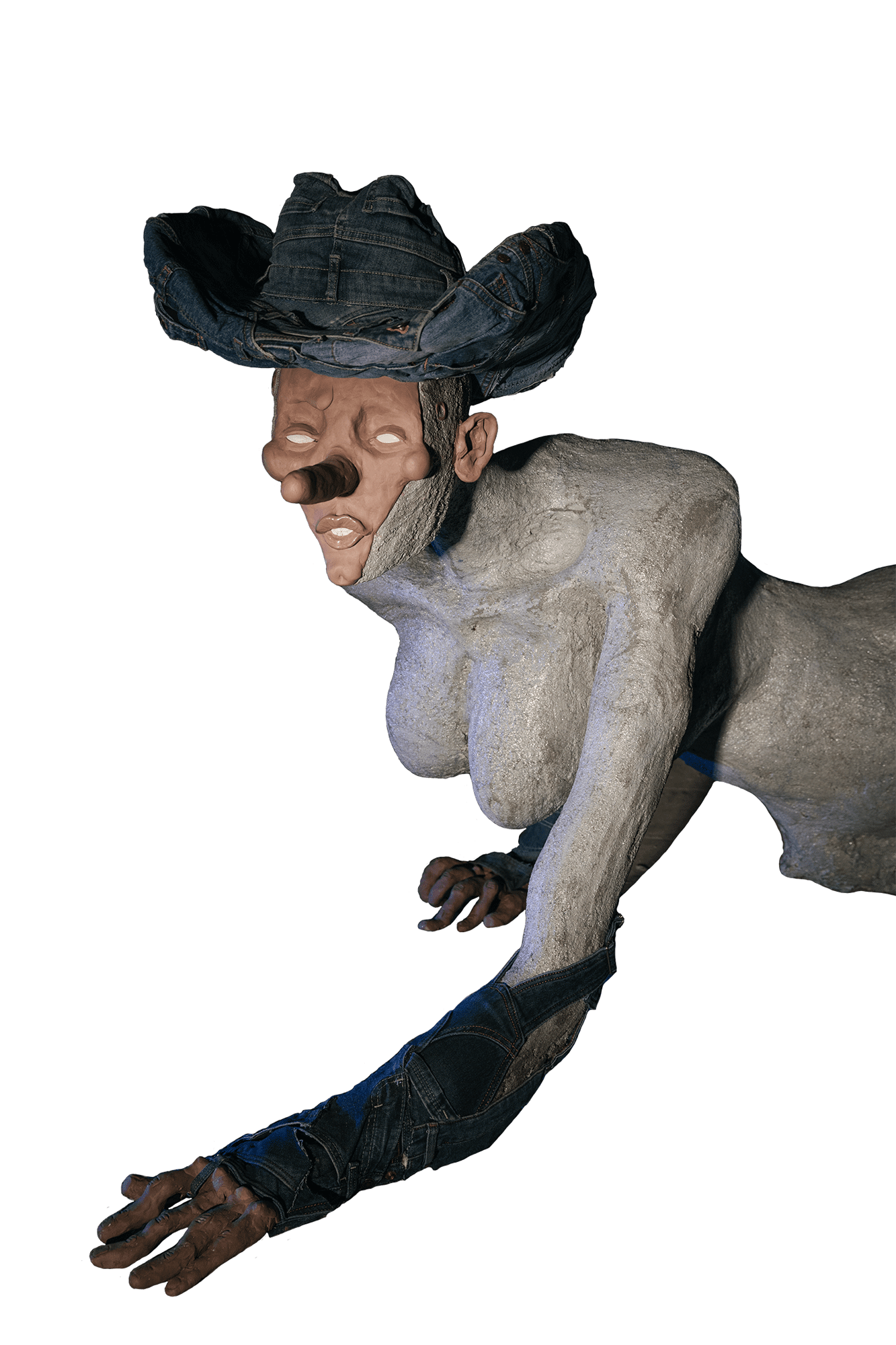

I have always been really into your sense of style. And I can see that you apply part of yourself to Miss Väike-Ameerika and Christina's Sacrifice. Could you tell me how much are they an extension of yourself or rather you an extension of them?

These cowgirl sculptures are certainly closely tied to my own body. They are my idealized selves, but also embody something sinister and sardonic. Their distorted proportions and larger-than-life size might be some sort of commentary about how much space I take up as an American, in every sense. I have a kind of push-pull relationship with them like they give shape to my darkest and most shameful desires. Not in a kinky way necessarily, but in a consumer culture object-commodity-fetishism way. I've placed Christina's Sacrifice in front of stylized buildings twice now, she’s always crawling toward that house on the hill, seeking the interior-decorated comfort it promises. I think she's craving the fleeting sense of completeness that consumer culture promises and chooses to believe in that myth.

Anyone who sees me in public knows I'm into denim. I hope to dive deeper into denim in a future exhibition because there's so much to explore. Denim as a status symbol, as social currency, especially in Soviet Estonia's parasocial relationship with American culture, denim as an American-coded industrial export from China and Bangladesh, the history of indigo, Levis and westward expansion, the Y2K style revival, Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake... there's so much there to unpack. Exploring these connections could be an entirely new body of work and I hope I can create it one day!

Zody Burke (b.1991, Manhattan) is an American multimedia artist and musician who is currently living and working in Tallinn, Estonia. She creates cyphers through sculpture and sound, through which to cartograph the complexity of American identity within late capitalism, explore parallel inherited cultural mythologies & their relationship to truth, and interface world-building with geological time. Her material practice ranges from ceramic high-relief to experimental music, large-format sculpture, video, illustration and fiber work. Post-pandemic, she has recently begun to show work around Europe and the United States.